The Bioguy: Getting to Know Hanna Gray Fellow Kevin Cox

Danforth Center Postdoctoral Associate Kevin Cox, Jr, PhD, remembers where he was when he first learned he had been selected as a Hanna H. Gray Fellow: “I had just completed something at the lab bench, then walked back to my desk to check my email. When I opened it, I shouted out loud and ran a victory lap around the lab.”

The Howard Hughes Medical Institute grants the Hanna H. Gray Fellowship to only 15 scientists nationally. The prestigious award includes a $1.4 million investment in a postdoctoral researcher’s career as they transition to principal investigator and begin to set up their own laboratory.

Dr. Kevin Cox with the 2019 class of HHMI Hanna Gray Fellows (Courtesy: HHMI)

“Being a Hanna Gray Fellow is an extraordinary opportunity,” said Cox. “Meeting the other fellows was so inspiring. We all want to make a change, make better science, make science more diverse, and help the community.”

Local Kid Makes Good

Growing up in Florissant, MO, in the Hazelwood School District, Cox loved science and wanted to be a doctor. “I wanted to be a pediatrician, but then I met microbes,” said Cox. “These tiny little objects have so much power—to hurt us, to heal us.”

During his junior year at the University of Missouri—St. Louis, he landed a lab assistant job at the Danforth Center. “I was fascinated to learn that plants can get sick just like humans get sick. And sick plants lead to so many problems… less food, higher prices, even illness. Pathology allowed me to merge my love for microbes and plants.”

Cox completed his PhD in plant pathology at Texas A&M University, then landed a postdoctoral position back at the Danforth Center with Principal Investigator Blake Meyers, PhD. “I always knew I wanted to come back to St. Louis—it’s my home. And the Danforth Center made that possible.”

Dr. Kevin Cox in his studio setup where he records his explanation for science for the general public (and where he is occasionally found playing video games).

Cutting-Edge Research

Kevin’s work today involves genetics, bioimaging, and plant pathology. “I’m figuring out which genes are key for plants to defend themselves against microbes,” said Cox. “When we get sick, our white blood cells ramp up. Plants have a different way of defending themselves. Mainly they use certain proteins that detect pathogens and notify the plant that it’s under attack and to activate a defense response, but right now we don’t know which genes are critical to the process. I hope to change that.” Kevin’s work focuses on using a technology called spatial transcriptomics. This is a high-throughput gene expression technology that will allow Kevin to sequence those genes that are key for plant defense and locate where they are expressed in the plant.

In addition to his sequencing work with Meyers, Kevin also works closely with Danforth Center Principal Investigator Kirk Czymmek, PhD, the director of the Advanced Bioimaging Laboratory. By combining this sequencing technology and imaging, Cox aims to study plant-microbe interactions at the single-cellular level—or at least try to do so.

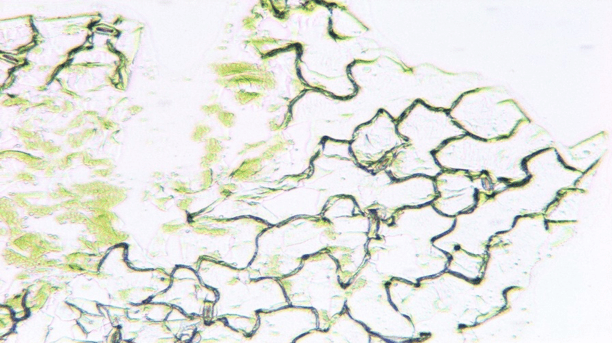

“It hasn’t really been done before. We currently have a map, but imagine a map without state borders or highways. I’m trying to fill in the landmarks so that we know where those genes are being expressed in the plant.”

Why it matters: If Cox’s project succeeds, it will help the entire plant community. Not only will it help in the breeding of crops that can better defend themselves against microbes, but it may help in the discovery of other key genes as well, such as those used in drought stress or salt tolerance.

An image from Dr. Kevin Cox’s research taken in the Advanced Bioimaging Lab: a very thin section of a plant leaf showing individual cells. (Credit: Danforth Center Advanced Bioimaging Laboratory)

Teach the Children

Cox is an educator in his spare time, serving as a science ambassador at Danforth Center STEM Splash Days: “I feel an extra responsibility as a Black PhD in science. I have a responsibility to help inspire the next generation. I want kids today to have what I didn’t have: a Black scientist role model.”

And “Bioguy”? That started as a gamer tag and is now a full-fledged persona: “I started making funny skit videos and Bioguy came to life. Now it’s the name I use for gaming and science communication videos. I like to make people laugh while I teach them something.”

How He’s Been Impacted

“The Hanna Gray has had a huge impact already, mainly that’s because of all the attention I’ve been getting. That has been amazing! It has helped put me in a conversation with other Black scientists who want to reach out and talk to me, people who want to hear my story. In sharing my story, I hope I can inspire another kid like me to pursue science.”

The Need

Danforth Center scientists represent the nation’s best and brightest plant scientists. They are very good at securing grants and fellowships, but even those awards cannot cover all operating expenses. Remaining support is provided by generous individuals and donors to the Danforth Center Impact Fund. To learn more about the many ways you can support work like this, click here.

About

A version of this story originally appeared in the Leaflet, the free newsletter of the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center. Sign up to receive more stories like this straight to your inbox.