Better Rice for a Changing Climate: How Dr. Bing Yang’s Research is Helping Feed the World

“Small farmers grow rice in the paddy field. There are no machines. It must be cultivated by hand. Sometimes you use water buffalo to help plow the field. You cut the rice by hand with a machete,” says Bing Yang, PhD, Danforth Center principal investigator and professor of plant science at the University of Missouri - Columbia.

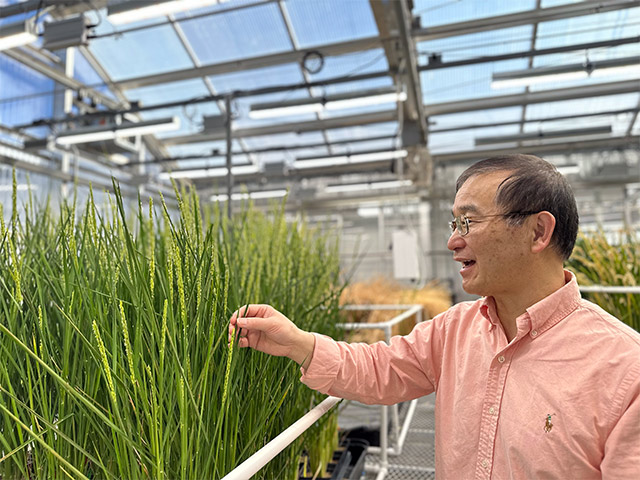

Yang is speaking from personal experience. He was raised in a smallholder rice farming family in Szechuan province. “Rice research is personal for me. Rice production and harvest matters to my family—and to millions of other small-scale farmers.” Today, Yang is an internationally recognized expert on rice bacterial blight—and the developer of cutting-edge biotechnology tools that are helping speed rice research.

Rice is one of the world's most important staple crops, providing nourishment to billions of people around the globe, especially in Asia and Africa. In developing countries, smallholder rice farmers play a critical role in feeding the population, even while using traditional farming methods that have been passed down for generations. Rice is not just a source of food, but a way of life and a livelihood.

We still face challenges ahead, but I believe we can help farmers effectively control bacterial blight and eliminate the epidemic.

Bing Yang, PhD,

Danforth Center Principal Investigator

Fighting the Blight

However, rice harvests are down. In 2022 rice production shrank by up to 10% in some countries. Rice farmers are already seeing the effects of a changing climate: there are more frequent floods and droughts. Droughts stress the plants and make them more susceptible to disease. Floods create the kinds of warm, moist environments in which many pathogens thrive.

One of the most destructive scourges is rice bacterial blight, an infectious disease created by the pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo). The disease is most severe in southeast Asia but is increasingly damaging in West African countries, and results in substantial yield loss of up to 75%. There are no chemical remedies for rice bacterial blight, so inborn disease resistance in the crop is crucial.

The Yang lab has a dual focus: (1) understanding bacterial blight better, and (2) developing the gene-editing tools to do something about it.

For Dr. Yang, rice is personal. He grew up on a small paddy farm in Szechuan. Today, he is a leading expert on rice bacterial blight—and the inventor of cutting-edge biotechnology toolkits to speed rice research.

“With better understanding of how diseases infect plants, combined with advanced biotechnology tools, we can develop genetic resistance in rice varieties,” says Yang. “Our goal is to give smallholder farmers seeds and tools to manage blight disease and reduce harvest losses.”

In 2019, Yang and an international team of researchers successfully used CRISPR-Cas9 technology to edit the genes that make the rice plant vulnerable to blight. Trials showed that the gene-edited rice lines were endowed with robust, broad-spectrum resistance. The findings were published in Nature Biotechnology.

Then in 2020, regulators in the United States and Colombia classified the gene-edited blight-resistant rice as equivalent to conventional varieties. The new blight-resistant varieties can now be used to introduce the resistance trait into many different types of rice via standard breeding strategies.

“We still face challenges ahead,” says Yang, “But I believe we can help farmers effectively control bacterial blight and eliminate the epidemic.”

Widespread Implications

Because rice is a model crop, the Yang lab can ultimately apply their research to the improvement of other grass species like corn, sorghum, wheat, and switchgrass. And the tools that the Yang lab is developing aren’t just limited to his lab. “It’s important to me that we share our knowledge. We make our biotechnology toolkits available to other scientists to use in their research, so these powerful tools can have a bigger impact in advancing plant science research,” explains Yang.

The Need

Dr. Yang was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the world’s largest general scientific society. He earned his place in this prestigious group due to his distinguished contributions to plant pathology and gene editing. Scientists like Dr. Yang receive support via early project funding, technology, and cutting-edge infrastructure from generous donors like you. Please consider a gift today.

About

A version of this story originally appeared in the Leaflet, the free newsletter of the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center. Sign up to receive more stories like this straight to your inbox.