A Return to the Wild: Sampling Soil on the Missouri Prairie

By Stewart Morley, PhD, Research Scientist in the Allen Lab

Have you ever heard of the prairie chicken? I hadn’t—until a recent conversation with incoming Danforth Center President Giles Oldroyd, PhD, who mentioned their decline. Of course, I thought I knew what a chicken was, but a prairie chicken?

Look them up—they’re actually quite beautiful birds, and they were once abundant across the Midwest, with populations numbering in the hundreds of thousands.

Today, it is estimated that fewer than 500 remain in Missouri.

It’s not hard to guess why this once-common species has become a rare curiosity. The largest culprit? Habitat loss—specifically, the transformation of native prairie into agricultural farmland.

Now before we jump to bemoaning modern agriculture, let’s take a moment to appreciate its accomplishments. Industrialized farming is truly a feat of human innovation. At no point in time have we been able to produce as much food as we can now. Modern agriculture is feeding billions, and it’s no wonder that when early farmers arrived in the Midwest, they took advantage of the rich prairie soils to plant farms. From a production point, it made sense. The prairies were vast, so, surely, we could stand to lose a little to support a lot?

As human populations have continued to grow more farms are needed to feed us. Over time, our little nibbles into the prairies wound up mostly replacing them.

However, we’re now starting to reconsider that approach.

Learning from Nature

This summer, researchers from the Allen, Bart, and Bravo labs traveled to natural prairies across Missouri, collecting soil samples to study the microbes hidden beneath our feet. This sampling occurred in prairies that have never been disturbed and remain as you would have encountered them for many centuries. The sites were selected in collaboration with the Missouri Prairie Foundation, whose conservation work on these prairies has made this research possible.

Researchers from the Danforth Center collect soil samples of undisturbed prairie ecosystems. Their goal is to learn more about its naturally occurring microbiomes and determine how we might use that knowledge to improve agricultural practices to benefit both people and the planet.

The project aims to compare the microbiomes of these undisturbed prairies to those of heavily farmed land. Why? Because healthy soils support more than just wildflowers and insects; they also enable farmers to grow better crops with larger harvests. This collaborative research is part of a broader initiative called the Subterranean Influences on Nitrogen and Carbon (SINC) Center, which aims to reduce synthetic fertilizer inputs on agricultural fields by 12%, an achievement that would reduce fertilizer costs for farming families and carbon emissions equal to removing one million vehicles from the road.

By using high-throughput DNA sequencing to analyze the soil samples, Danforth Center scientists hope to identify microbial communities that naturally promote soil fertility and plant health. The data provided is precise enough to describe the taxonomic diversity present in each sample. Comparing these communities to those found in farmland may help us discover which microbes are beneficial—and which might be doing more harm than good. Here are some of the key questions we’re digging into:

- How do the soil microbiomes differ between undisturbed prairie soils and cultivated agricultural soils?

- Does microbial diversity in agricultural soils improve crop yields?

- Can we positively influence the diversity of agricultural soil microbiomes?

- Can we leverage soil microbiome composition to improve the health of agricultural crops?

- How can microbial communities in natural prairie soils enhance our knowledge of microbial communities in agricultural fields?

- And perhaps the biggest question/goal is, can we artificially create microbial consortia that reduce agricultural inputs while improving crop growth, health, and yields?

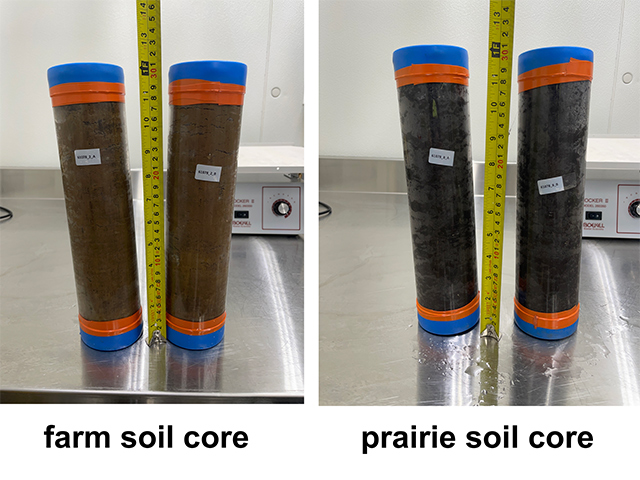

A side-by-side comparison of soil samples taken from agricultural land and soil samples from an undisturbed prairie show a difference that's visible even to the naked eye. To better inform how we might be able to mimic nature in our agricultural practices, Danforth Center researchers hope to learn more about what separates the two soils on a microbial level.

Why It Matters

The goal of answering these questions is ambitious but simple: use insights from nature to grow more food with fewer synthetic inputs, preserving the wild land we have left while making better use of the farmland we already cultivate.

In other words, the same systems that once nurtured thriving prairies might help us build a food system that can last—without erasing what's left of the wild.

I think the average person could agree that the more natural we can make our processes from farming to food to diet, the better it is for people and the planet.

Being a part of this project makes me hopeful that we as a species can innovate and create solutions for the problems we face. Plant science has the power to create such solutions, and this prairie soil sampling project is just one of many ongoing initiatives that are tackling some of the major existential threats we face as a species.